Cultural Dimensions

DECIDING

Who and How People in Different Cultures Decide

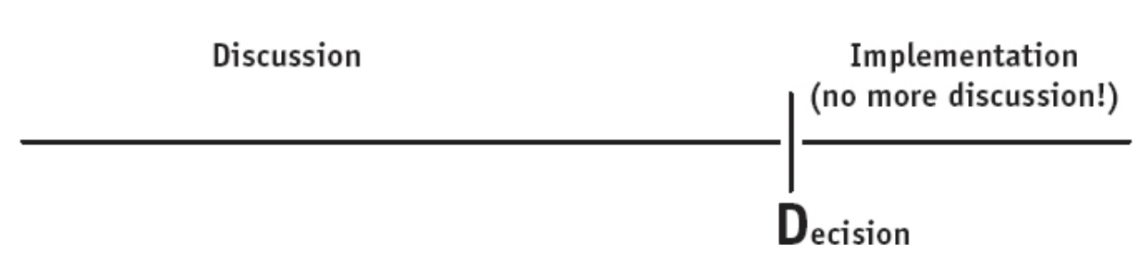

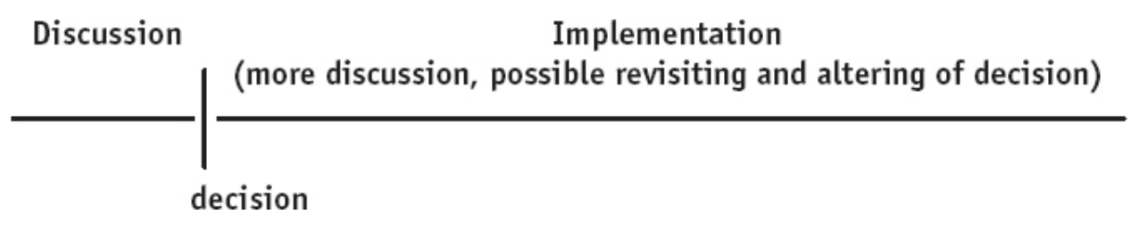

The Deciding scale measures the degree to which a culture is consensus-minded.

According to Meyers, we often assume that the most egalitarian cultures will be the most democratic, while the most hierarchical ones will allow the boss to make unilateral decisions. But this is only sometimes the case. Germans are more hierarchical than Americans but more likely than their U.S. colleagues to build group agreements before making decisions. The Japanese are both strongly hierarchical and strongly consensus-minded.

Key Characteristics

|

CONSENSUAL |

TOP DOWN |

|

|

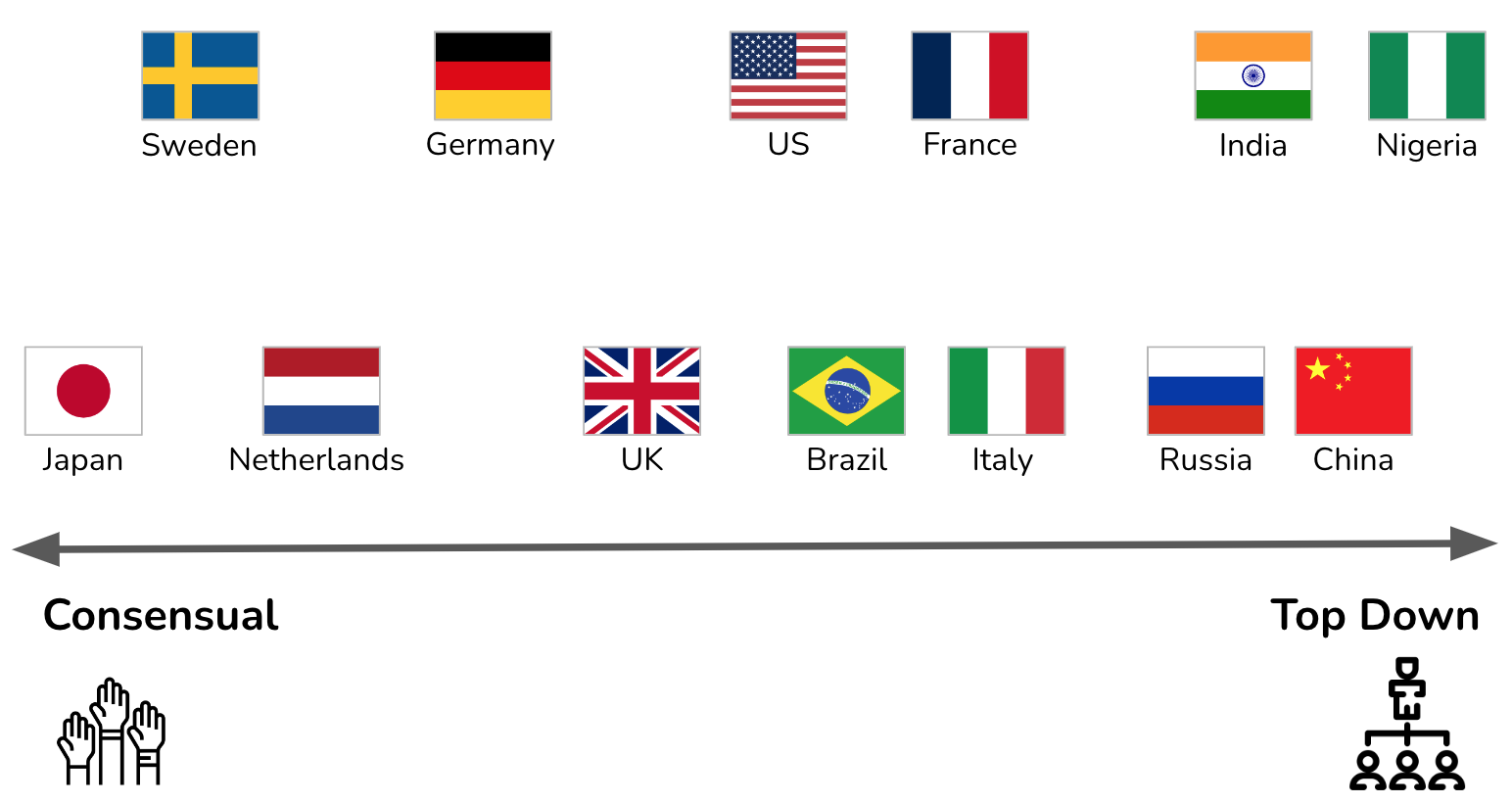

COUNTRY COMPARISON

The chart shows examples of where certain countries fall on the decision-making scale.

THE LINK BETWEEN LEADERSHIP & DECISION-MAKING

In the following video, you will see how different cultures approach the decision making process.

HISTORICAL ROOTS OF THIS DIMENSION

As with all cultural characteristics, these differing styles of decision-making have historical roots. American pioneers, many of whom had fled the formal hierarchical structures of their homelands, put emphasis on speed and individualism. The successful pioneers were those who arrived first and worked hard, regarding mistakes as an inevitable side-effect of speed.

Americans therefore, naturally developed a dislike for too much discussion, preferring to make decisions quickly.

Get in Touch With Us